The twin impacts of the worst global health pandemic in over a century and a price war standoff between the world’s top oil producers Saudi Arabia and Russia has driven oil prices to record lows that could soon fall into single dollar digits per barrel.

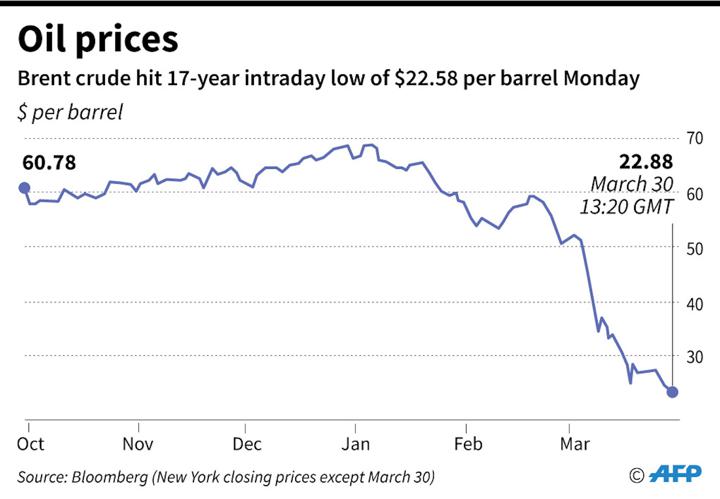

On March 30, spot prices for both global benchmark Brent crude and US-benchmark West Texas Intermediate (WTI) fell to levels not seen since 2002. Brent was trading around $23 per barrel while WTI sank briefly below the psychologically important $20 per barrel price point.

Within 24 hours of trading prices had recovered slightly, with Brent up 38 cents per barrel and WTI up 79 cents, but more dips are expected before substantial rises. Single dollar digit oil prices, not seen in decades, now seem a distinct market possibility, analysts say.

Prices for Brent and WTI have tanked by more than 50% in the past two weeks, thanks to the double whammy of the Covid-19 pandemic and Riyadh versus Moscow stand-off over oil production levels.

The market has now flipped dramatically from “backwardation”, where the forward price of oil futures contracts is lower than the prevailing market price, to “contango”, where the opposite price relationship holds.

That trend has not been seen in decades, underscoring the uncharted waters oil markets have entered with prices down more than 65% since the start of the year.

The downward drivers for oil prices are excess production, demand destruction and a corresponding buildup of inventory levels. The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies said last week that concern about the availability of storage will continue to put severe pressure on prices.

The economic impact of the Covid-19 pandemic and its effect on future oil demand is being forecasted variously, to say the least.

Consultancy Rystad Energy said in a March 30 note that around 16 million barrels per day (bpd) of oil demand will be lost in April, while oil supply chains are being broken due to “unbelievably large losses in oil demand, forcing all available alternatives of supply chain adjustments to take place during April and May.”

“We see in this coming month of April what could be a 20 million bpd decline in oil demand. It’s unprecedented,” Dan Yergin of IHS Markit told CNBC on March 30. “That’s six times larger than the biggest downturn during the [2008-9] financial crisis period,” he added.

However, while the problem of oil demand destruction due to the Covid-19 pandemic will likely take months or even longer to play out, the impact of the oil price war between Riyadh and Moscow will be felt more than originally anticipated.

As global oil storage capacity fills up, including on emergency floating facilities, the lack of storage will backfire on the Saudis and Russians, as both opportunistically seek to lock in and steal market share from one another by cranking up their oil production spigots.

Extra production

Analysts say there will soon be nowhere to store all of the extra production that both countries are producing. This will inevitably lead to production closure, a rare occurrence in global oil markets that are usually clamoring for more of the precious black commodity.

As production closures ensue and economic activity ideally picks up as the Covid-19 pandemic eventually eases, markets could return to some form of price sanity and market equilibrium, with a new price floor that could help many producers shore up their balance sheets and plan ahead.

Under one scenario prices will return to the $30s and possibly the low $40s by late this year. WTI future are expected to trade at an average of $34.95 per barrel in 2020, The Wall Street Journal said yesterday, citing a poll of 11 major banks.

The banks also forecast that Brent crude will average $38.12 per barrel this year, its lowest price point since 2004. For the second quarter, however, Brent is expected to stay below $28 per barrel and WTI below $25, the same poll showed.

Though these forecasts show a rise in prices from their current levels, they are still too low for Saudi Arabia and Russia to even come close to their so-called fiscal break even points, the price that oil needs to reach for the two to balance their books.

Saudi Arabia, for its part, needs oil at a whopping $85 per barrel to balance the its national fiscal accounts, according to the International Monetary fund (IMF), while Russia needs prices in at least the mid $40s.

-

![An oil pump jack is pictured at the Abino-Ukrainian oil and gas field in the Krasnodar region, Russia. Photo: AFP Forum via Sputnik/Vitaly Timkiv]()

An oil pump jack is pictured at the Abino-Ukrainian oil and gas field in the Krasnodar region, Russia. Photo: AFP Forum via Sputnik/Vitaly Timkiv

Russia may be able to endure this prolonged low price environment longer than Saudi Arabia, which could be forced to raise cash through international bond sales to say afloat.

But for the foreseeable future raising cash when at least one third of the world is under lockdown and the global economy headed into what could be a multi-year recession seems a fool’s errand at best.

Moreover, the hit to Saudi coffers may be a blow that could take years to overcome, just as the country was supposedly trying to wean itself off of oil revenues for economic sustenance.

With many speculating who will blink first in the Saudi-Russian oil price struggle, it seems increasingly that the Saudis will fold first.

However, the question has changed from who will blink first to whom will be hit the hardest. The answer: US shale and other oil producers.

The resurgence of US oil production over the past decade, enabled by the wonders of fracking and hydraulic drilling, has revolutionized global oil markets and transformed the US into the top global producer.

That has allowed the US to grab market share from entrenched global oil as well as gas producers. However, America’s brief two-year reign at the top of the global oil production hierarchy could soon end.

Edward Bell, commodities analyst at Dubai-based bank Emirates NBD, said that the current rate of rig closures in the US means caused by falling prices will lead to an estimated 750,000 bpd decline from the second quarter onward.

That, he says, will drive US output of around 13 million bpd at the start of the year to “down below Saudi Arabia or Russia by the end of the year.”

The implications for the US are multi-faceted, ranging from a painful economic downturn in the country’s until recently vibrant energy sector, with a ripple effect through the overall economy, to massive oil industry layoffs.

Those, in turn, will lead to the probable reorganization and insolvency of several US oil and gas companies, especially smaller players that were already burning cash on their balance sheets to stay operational.

On a larger scale, it will also mean a loss of the recently recouped geo-political power the US has enjoyed from ramped up oil production. Small wonder, then, that US officials are publicly calling on Russian and Saudi leaders to stop their supply war and allow prices to start floating upwards again.