Insiders have revealed division within the Bank of Japan on the timing of its grand plan to call an orderly end to years of massive stimulus, which the BOJ implemented on Tuesday.

The central bank’s strategy began look troubled in December – with the economy lacking momentum – when Governor Kazuo Ueda met with two deputies at the bank’s head office in Tokyo.

Inflation was slowing more than expected, complicating the bank’s plan to end negative interest rates by March or April and then follow quickly with further increases. The officials considered two alternatives.

ALSO SEE: China Bonds Bonanza Fuelled by ‘Asset Famine’, Property Woes

The first option was to wait for signs of economic improvement and then go ahead as planned. The second was to end negative rates but hold off on subsequent increases.

Ultimately, the MIT-trained Ueda went with the second option, allowing Japan to shed its title as the last country with negative interest rates but leaving it short of its hoped-for normalisation and still facing years of near-zero rates that pressure the hard-hit yen.

“With the economy lacking momentum, there was a growing feeling within the BOJ that inflation might not stay around 2% that long,” said one person familiar with the deliberations, referring to the bank’s key target.

“The BOJ leadership probably realised that time was running short, if they wanted to end negative rates.”

The decision was complicated by differences between Ueda’s two deputies, as well as the governor’s wavering on the exit timing. This is the first report about the existence of the two plans, and other details about the deliberations.

This account is based on interviews with 25 incumbent and former central bank officials with direct knowledge of the interactions, or familiar with the personalities and dynamics of the bank’s leaders, as well as five government officials in regular contact with BOJ officials.

They all spoke on the condition of anonymity as they were not authorised to discuss the matters publicly, while a BOJ spokesperson said the bank would not comment on the deliberations.

Small-business owners have also told how the policy shift could unfold across an economy battered by decline and deflation.

On Tuesday, the BOJ drew the curtain on eight years of negative rates and other remnants of unorthodox policy, delivering its first increase in borrowing costs since 2007.

“It’s a watershed moment for Japan and for central banks across the world, as it finally puts an end to abnormal monetary stimulus,” former BOJ official Nobuyasu Atago said.

But, he said, it could take several years for short-term rates to move up to even 1%.

Many resort towns, traditional inns struggling

Even a slight rise in interest rates could send tremors through struggling local economies in Japan, reflecting how deflation and a diminishing population have squeezed demand.

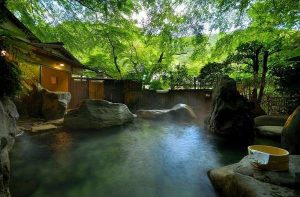

“The prospect of higher interest rates has become a significant concern for traditional inns,” said Koji Ishida, who runs a hotel company and heads the local tourism association in Yugawara, a hot-spring resort southwest of Tokyo known for its ryokan, or traditional inns.

In autumn, Ishida received a frantic call from the family that owns one of the town’s most storied ryokan, saying it was nearing collapse and asking for help.

“As neighbours, we needed to help them,” Ishida said. He worried the failure of a prominent ryokan could tarnish the image of tourism-dependent Yugawara and trigger “a chain reaction of bankruptcies”.

Seiranso, a 94-year-old ryokan known for its mountainside outdoor bath at the foot of a waterfall, last month filed for bankruptcy protection with around 850 million yen ($5.7 million) in debt, including pandemic loans.

Under those proceedings, it aims to turn itself around with backing from Ishida’s company, according to its website. A lawyer for Seiranso declined to comment.

Almost one-third of ryokan lost money in the last financial year, according to data from the Japan Ryokan and Hotel Association, an industry group.

“The industry needs zero-interest rates,” said Masanori Numao, whose family runs a ryokan in Kinugawa Onsen, a hot-spring resort in Nikko National Park, where their roots go back more than 300 years.

Forty years ago, Kinugawa was thriving; after sunset there were “beautiful geisha”, the clatter of wooden geta clogs and laughter from karaoke bars that lined the narrow streets, Numao said.

Today, tourists sometimes photograph derelict hotels abandoned after the bubble economy burst in the early 1990s.

Ryokan owners struggle to renovate ageing buildings because banks are unwilling to lend them more, making it difficult to attract tourists, Numao said.

Higher interest rates would increase pressure on hot-spring towns like Kinugawa, he said. “The government is just watching resort towns drown.”

Undoing Kuroda’s big bazooka policy

In taking over the BOJ last April, Ueda was mandated to dismantle the radical stimulus of his predecessor, Haruhiko Kuroda.

Kuroda’s “bazooka” approach initially helped boost stock prices. But it crushed bank margins and caused unwelcome yen declines that lawmakers feared could hurt voters through rising living costs.

Ueda and his deputies were unanimous on the need for an exit, but not on the timing.

Choosing the second option mended, at least momentarily, the quiet tension between the two deputy governors, career central banker Shinichi Uchida and former bank regulator Ryozo Himino.

Ueda, Uchida and Himino did not respond to questions. Uchida was cautious about ending negative rates too hastily, believing that the BOJ should allow the economy to run hot by keeping ultra-low rates for a prolonged period.

By contrast, Himino favoured an early exit from what he saw as excessive monetary support that could sow the seeds of a future bubble. As an outsider, Himino wasn’t afraid to challenge some of the bank’s traditions.

At one informal meeting late last year, he complained about the BOJ’s management style and suggested changes, ruffling feathers among some officials within the institution, according to two people with knowledge of the matter.

Throughout the discussions, Ueda would listen silently and rarely spoke up. People who know him say the governor was neither a hawk nor a dove.

Having studied under former Federal Reserve vice chairman Stanley Fischer, who also taught former central bankers Ben Bernanke and Mario Draghi, Ueda combined faith in economic models and a sense of pragmatism.

But, he was not quick to make decisions, opting to analyse various options thoroughly until the last minute.

“He’s a pure academic who’s great at comparing data and strategies,” said a person who has known Ueda for decades. “But making quick, decisive decisions isn’t his strength.”

While the two deputies rarely exhibited differences in public, it was usually Uchida who prevailed. Ueda relied heavily on Uchida’s expertise on the technical aspects of the bank’s monetary tools.

Uchida was also the main interlocutor with officials from Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s government, sounding out their views on monetary policy and laying the groundwork for an exit.

Declining yen hurting households

Kishida’s administration had been nudging the BOJ to phase out stimulus in hope it would slow declines in the yen that were hurting households through higher food and fuel costs.

“The government hopes the BOJ conducts monetary policy appropriately towards sustainably and stably achieving its price target accompanied by wage increases, with an eye on economic, price and financial developments,” a spokesperson for the prime minister’s office said.

Once there was consensus the BOJ would go with the second option, Uchida proceeded with the next step of preparing markets.

In a speech in Nara in February, Uchida hinted at what a post-negative rate monetary policy would look like.

Tuesday’s policy shift roughly aligned with those clues.

Ueda’s choice of the second option means the BOJ will keep rates at zero for a prolonged period, delaying Japan’s return to normal borrowing costs, said five of the sources familiar with the bank’s thinking. It will likely take years to reduce the bank’s balance sheet, which ballooned after heavy asset-buying, three analysts said.

There is near-consensus among BOJ watchers that the bank will move very gradually, and allow short-term rates to rise to around 0.5% over several years.

“Given Mr Ueda’s very cautious character and his focus on building consensus within the board, he will likely take plenty of time and proceed carefully in normalising policy,” former BOJ economist Hideo Hayakawa said.

Yen may fall further

The yen fell to a four-month low on Tuesday after the BOJ decision to end its negative rates, which was widely anticipated. Meanwhile, the dollar strengthened ahead of the Federal Reserve’s latest outlook for rates.

With most investors having already priced in a change, the yen dropped more than 1%, and by late on Wednesday, it was down about 1.1% at 150.775 to the dollar.

However, analysts said the currency was at risk of falling further and could touch multi-year lows.

- Reuters with additional editing by Jim Pollard

NOTE: Additional details (on the yen) were added to this report on March 20, 2024.

ALSO SEE:

Bank of Japan Ends Negative Rates, as Ueda Normalises Policy

BOJ Views on Inflation, Pay Rises Put Spotlight on Rates Shift

Japan’s Salaries Surge Could See BoJ Turn to Tightening

BOJ Not Afraid of Cost of Phasing Out Stimulus, Ueda Says

BoJ Dismiss Rumours Ultra-Easy Policy Will be Ditched

Yield Curve Call Sparks BOJ Policy Doubts as Yen Struggles

New BOJ Boss Ueda Sees Wages Rising, Global Rebound