China’s world-beating auto industry is staring into an abyss.

Its carmakers and dealers are struggling to make money and fierce competition has left scores of firms on the brink of collapse. Meanwhile, many thousands of cars are being sold at a fraction of their price, or left abandoned altogether in automotive graveyards.

Those are the findings from an extensive investigation carried out by Reuters, which reviewed thousands of car-sales listings and hundreds of government documents, state-media reports, court filings and consumer complaints, and interviewed with some 20 industry players, including dealers, buyers, analysts and manufacturing executives.

Also on AF: Huang Voices Disappointment After China Bans Nvidia’s AI Chips

Industry executives say making a profit is nearly impossible for almost all automakers in China, where electric vehicles start at less than $10,000 — in stark contrast to the US, where carmakers offer just a few under $35,000.

Most Chinese dealers can’t make money, either, according to an industry survey published last month, because their lots are jammed with excess inventory.

At the root of the problem are years of subsidies and other government policies aimed at making China a global automotive power and the world’s electric-vehicle leader.

China has more domestic brands making more cars than the world’s biggest car market can absorb because the industry strives to hit production targets influenced by government policy, instead of consumer demand, Reuters found.

And to tackle the resulting oversupply, Chinese automakers and dealers have resorted to unusual practices that suggest a potential shakeout looms for the world’s largest car industry.

A policy shambles

The seeds of the current state of China’s automotive market were planted in Beijing, where national policymakers as far back as the 1990s wanted to put China in the driver’s seat of electric vehicle production.

In 2009, Beijing launched a programme to encourage carmakers to produce EVs and consumers to buy them, backed by billions of dollars in subsidies.

By 2017, EVs hadn’t taken off. That year, Chinese government officials drafted a car-making policy blueprint that outlined a goal of producing 35 million vehicles a year by 2025 — roughly double the US annual sales record.

The push for EVs became particularly profound as an overheated property sector began to bite local governments and unsold condo blocks began weighing on the Chinese economy. The automaking blueprint became a timely alternative economic pillar for local governments that had begun to rely on land sales and real-estate tax revenue.

The 2017 plan helped fuel a scramble by local authorities to woo EV makers. And by last year, China came close to the target, building more than 31 million vehicles, according to industry body CAAM.

This competition created a playbook across China: Local governments provide incentives to automakers and demand production and tax-revenue targets in return. Automakers often focus more on hitting those targets than turning a profit. Over time, manufacturers that might fail in other markets are often kept afloat by local governments that have a vested interest in their survival.

“When there is a directive from Beijing that this is a strategic industry, every provincial governor wants the car factory. They want to be in good shape with the party,” said Rupert Mitchell, an Australia-based macroeconomics commentator who previously worked at a Chinese EV startup. “Ultimately, what happens is that it makes the existing auto sector double down on investment.”

Some big wins

Governments that bet on the right automaker saw massive gains. In 2021, for instance, the county government of Changfeng, in Anhui province, attracted auto giant BYD with super cheap land. In return, the county, whose main industry was making traditional flatbread, got a BYD mega-factory.

Over five years, BYD bought up 8.3 square kilometres of land in Changfeng at an average price 40% below that paid by other buyers, Reuters determined from property-sales filings published by China’s government. BYD didn’t address questions about the arrangement and other matters raised in this report. A person reached by phone at Changfeng county’s propaganda office said some of the reporting was inaccurate and declined to elaborate.

In 2023, the year after BYD started production in Changfeng, the county’s economic growth outpaced the national rate by 9.1 percentage points. Last year, it remained 5.6 percentage points higher.

The official People’s Daily newspaper lauded Changfeng in March for its remarkable growth, citing BYD as a major factor.

Two Communist Party officials in Changfeng tied to the BYD project, Fan Shaobin and Li Mingshan, received promotions to higher levels of government in 2024, notices published by the party’s Anhui Provincial Committee show.

Following a similar playbook. smartphone maker Xiaomi began buying land in Beijing’s Yizhuang district in 2022 for an EV factory. By 2024 it had purchased more than 206 soccer fields’ worth at an average price 22% below the rate others paid for industrial land, land-sales filings show. The city of Beijing required the plant to generate a minimum annual revenue of 47 billion yuan, about $6.6 billion, at full production, according to the filings.

A vicious cycle

While some governments won big, these policies multiplied overcapacity across the country, resulting in a price war that has now raged on for three years.

Concerns around price cuts have been such that in June, after BYD announced brutal new price cuts, the chief of Great Wall Motors, one of China’s oldest carmakers made a series of rare public statements alleging price wars were destroying the bottom lines of car companies and their suppliers, while also creating a mountain of debt.

“The EV industry’s Evergrande is already here,” Wei Jianjun said referring to China’s once-largest property developer that went belly-up in 2022 due to its more than $300 billion worth of debt. Automakers such as Geely and GAC Aion backed up Wei.

The only escape would involve letting many automakers fail, some analysts say. But many Chinese officials have resisted that tough-love path, which industry analysts say would risk mass layoffs and falling consumer spending.

That leaves automakers and local governments locked in an increasing downward spiral, said Yuhan Zhang, principal economist at The Conference Board’s China Center, a research group.

“They’re feeding each other, reinforcing each other, and that could trap the market in a vicious cycle,” he said.

He Xiaopeng, the CEO and co-founder of Chinese EV startup Xpeng, predicted in 2023 that each Chinese automaker would need to sell 3 million cars a year by 2030 to survive — and that only eight firms would be left standing. Xpeng sold 190,000 cars last year.

A few big players are hitting or approaching those volumes and appear positioned to benefit in a shakeout. In January, Geely said it wants to sell 5 million vehicles annually by 2027, more than double the 2.2 million it sold last year.

Industry leader BYD has also set ambitious targets for 2025, though its expansion has been slowing. In August, its quarterly profit fell for the first time in more than three years. Internally, BYD has scaled back its original plan to sell 5.5 million vehicles and now expects to move at least 4.6 million, Reuters reported this month.

Most industry players are selling a fraction of those volumes, but are still cranking up production – in at least three cases at the behest of government officials.

Last year, as state-owned automakers such as Changan, Dongfeng and FAW fell behind their private peers in the EV race, the national regulator of government-owned firms announced that it wanted the state companies to grow market share and production, rather than focus on profitability. Neither the automakers nor the regulator, the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission, addressed Reuters’ questions about the directive.

In July, Changan said it wanted to quadruple sales of new-energy vehicles by 2030. “We will work towards becoming a top ten global and world-class auto brand,” chairman Zhu Huarong said at a July 30 press conference.

Padding sales volumes

Meanwhile, some EV brands such Neta and Zeekr have resorted to inflating sales in recent years, with Neta doing so for more than 60,000 cars. The automakers arranged for cars to be insured even before they were sold, so the vehicles could be formally booked toward monthly sales targets.

Neta’s parent, Hozon, which is in bankruptcy administration, was one of China’s hottest EV start-ups just three years ago.

Meanwhile, Zeekr said in July the cars had been insured with mandatory traffic insurance to ensure their safety while exhibited, and that they were legally new when sold to buyers.

Neta and Zeekr exemplify industrywide padding of sales figures, much of it involving ‘zero-mileage’ used cars that have been insured and booked as sold, dealers and analysts say. Dealers and traders export those cars as used, often with the encouragement of local governments, or sell them domestically through gray markets.

In June, four regional dealer groups called automakers’ incentives “a disguised way of forcing dealers to falsify sales volume,” without identifying car companies.

Gotta keep peddling

Chinese brands now far outpace foreign rivals in delivering new models. Automakers have factory capacity to produce twice the 27.5 million cars they made last year, according to consultancy Gasgoo Automotive Research Institute.

The problem is especially acute in gasoline vehicles, for which demand has cratered in the past few years as Beijing encouraged EVs. At the same time, the number of EV factories proliferated as companies and local authorities piled in. AlixPartners, another consultancy, predicts only 15 of the 129 EV and hybrid brands in China will be financially viable by 2030.

And with greater production comes increased pressure to hit sales targets and gain market share.

Vehicle manufacturers in China are driven to keep selling and producing, even at deep losses, because this ensures cash flow, which is crucial to survival, said Liang Linhe, the chairman of Sany Heavy Truck, one of China’s largest truck makers.

“It’s like riding a bicycle: As long as you keep pedaling, you might feel exhausted, but the bike stays upright,” he told Reuters.

Grey markets and TikTok livestreams

The market conditions so created have left automakers with few options to deal with rising inventories. Some cars end up in grey markets, where cars can end up being sold at as much as a quarter of their listing prices.

In one showroom on the outskirts of Chengdu, Reuters reported locally made Audis being sold at 50% off. Similarly, a seven-seater SUV from China’s FAW is about $22,300, was on sale for more than 60% below its sticker price.

The deals were being offered by a company called Zcar, which said it buys in bulk from automakers and dealerships.

Zhou Yan, Zcar’s marketing director, told Reuters it can sell at deep discounts because it buys some vehicles directly from automakers in batches.

When Reuters visited Chengdu in June, livestreamers were touting a batch of GM’s Chevrolet Malibus. Zhou said Zcar had acquired more than 3,000 Malibus in China from SAIC-GM, the US automaker’s Chinese joint-venture entity, and was selling them for under $14,000 apiece, down from a sticker price of $24,000.

GM told Reuters that “authorized dealers are the only official channels for our vehicle sales,” and that Zcar “isn’t a dealer affiliated in any way” with SAIC-GM. It declined to elaborate.

Zcar subsequently told Reuters its subsidiary, Cheshi, had bought 3,428 Malibus primarily for wholesale distribution to dealerships, without specifying from whom.

Zcar added that it offers “popular, attention-grabbing models to attract customers to our stores” and often sells them at a loss. Its trade in the Malibus hasn’t been previously reported.

Some Audis were priced at half off when Reuters visited. Audi declined to comment on Zcar’s practices but told Reuters it doesn’t support grey-market trade, which harms the long-term value of its vehicles.

Zcars has now gone as far as to bring in TikTok influencers to sell off cars. On such live-streaming host, Wang Lihong, recently told his 1.25 million followers that Zcar was Sichuan province’s biggest seller of zero-mileage “used” cars.

He said they are usually available in March, June, September and December, “when dealers rush to meet the quarter or annual sales targets set by the automakers for cash rebates.”

“There’s no car that can’t be sold, only a price that isn’t right,” Wang said in a livestream in July.

‘The market will die!’

The flood of new cars has also made it harder for dealers to turn a profit, said Chen Keyun, a retired dealer in Jiangsu province. His assessment was backed up by four dealers who spoke on condition of anonymity.

And it has forced dealers to sell new cars at losses, or offload them to traders who sell them on as zero-mileage “used” cars. Just 30% of dealers are profitable, an August survey by the China Automobile Dealers Association (CADA) found.

In June, dealer groups in Henan and Sichuan provinces and the Yangtze River Delta aired their grievances publicly.

“We urge automakers to formulate sales guidance policies that align with market realities,” the Henan Automobile Industry Chamber of Commerce said in an open letter to unspecified automakers. “If the sales channels collapse, the market will die!”

Larger dealerships overpurchase inventory to hit automakers’ sales targets and obtain factory rebates, Chen said.

“If you have managed to sell 16 out of the 20 units targeted for the month, what will you do with the remaining four units on the very last day of the month?” said one dealer in Jiangsu. Selling those cars, even at fire-sale prices, would mean qualifying for a bonus of around 80,000 yuan, or $11,200, and put him close to break-even.

Lang Xuehong, deputy secretary-general of the CADA industry group, acknowledged dealers were selling at up to 20% below their cost. This was “unprecedented,” she told Reuters in a June 24 interview.

A zombie automobile graveyard

Meanwhile, some brand-new vehicles that aren’t sold end up in automotive graveyards. Local governments have strained to clean up abandoned-car lots, which consume land and create environmental hazards.

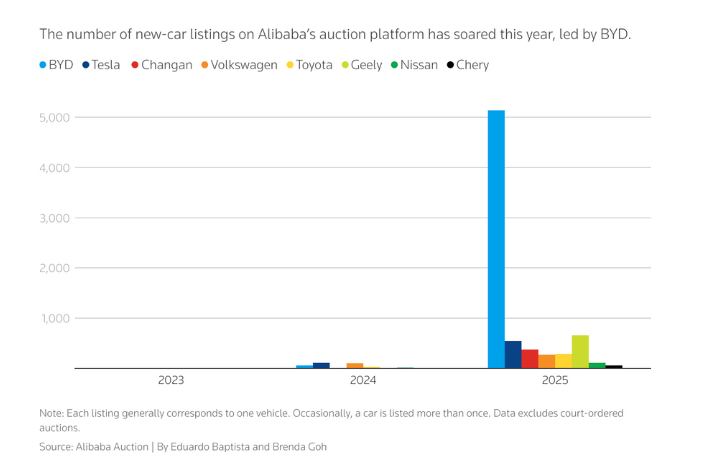

Other cars end up parked for the long term on auction sites, including those run by e-commerce giant Alibaba. Many get no bidders. A Reuters review of Alibaba listings identified more than 5,100 auction notices this year for brand-new BYD cars that had been insured and registered, up from 61 in 2024.

Chinese courts, too, have been holding auctions for new and unsold cars belonging to defaulted dealers.

One Alibaba listing in April 2024 that advertised a batch of 94 cars made by Dongfeng Honda showed photos of vehicles parked indoors. The white body of one was coated with grime, with the front seats covered in plastic sheets. Dongfeng didn’t respond to questions; Honda said it couldn’t comment on the activities of its authorized dealers.

Another clean-up ordered by a Shenzhen court involved nearly 2,000 cars built in 2018 by Denza, now fully owned by BYD. The vehicles were parked in Chengdu, Guangzhou and at BYD’s factory in Shenzhen after the buyer, ride-hailing firm Guizhou Qianxi, got into a dispute with Denza in 2020 over rebates and unspecified contractual matters.

The vehicles sat collecting dust until 2023, when the court put them up for auction. Court-appointed assessors found the cars had been barely driven and their interiors were brand-new. They had been left in various locations – including an area next to a grocery store where villagers hang their laundry.

The cars soon began appearing on social-media platforms. Livestreamers were selling the vehicles for as little as $9,000 – a quarter of their original price.

Consequences for the Chinese economy

Yet, despite the mess in the auto industry, sweeteners from local governments continue to flow.

In June, Guangzhou officials published a policy document that said the city wanted to foster up to three makers of “new energy vehicles,” which include fully electric cars as well as hybrids, to each produce 500,000 vehicles a year. In return, Guangzhou would award up to 500 million yuan (about $70 million) annually to each automaker that built new production lines and made 100,000 vehicles within three years. The city didn’t respond to a request for comment.

At least six other local governments between 2023 and 2025 issued policies to entice automakers to increase output, policy documents show.

The problem of overcapacity, meanwhile, is not limited to just the EV industry, but also others such as the property market that remains far from seeing any recovery, and the solar industry, which is currently in the middle of a shakeout. The issue is so deep rooted in the Chinese market that it has earned it own monicker — neijuan, or ‘involution’ — a term used to refer to hyper-competition that becomes self-destructive and incentivises irregular practices.

In recent months, though, Chinese authorities have started to sound alarm bells on the auto price wars, saying the competition was irrational and unsustainable. This summer, President Xi Jinping rebuked provincial officials, questioning why every province was racing to invest in a handful of technologies such as EVs and artificial intelligence.

The brewing crisis has larger implications for China’s economy, where the auto industry and related services comprise about one-tenth of gross domestic product.

Government policies that prioritise sales and market share often do so because of larger goals for employment and economic growth.

But with losses mounting for so many carmakers, there is growing talk among some industry analysts of a traumatic shakeout.

Still, three industry figures and two analysts told Reuters an abrupt shock is unlikely: Consolidation could take years, and local governments would probably support flailing automakers, containing the fallout.

“The problem of excess capacity in China is a systemic problem,” Michael Pettis, a senior fellow at Carnegie China research centre, said.

- Reuters, with additional editing by Vishakha Saxena

Also read:

Beijing Says it Will Rein in EV Sector’s ‘Irrational’ Competition

Local Officials in China Backed Export of ‘Zero-Mileage Used Cars’

China’s Top Paper Seeks End to Sale of ‘Zero-Mileage Used Cars’

China Plays Rare Earths Card in EV Tariff Negotiations With EU

Cargo Ship Carrying 3,000 Cars Ablaze Off Alaska, EV Fire Blamed

China Carmakers Told to Explain Sales of ‘Zero-Mileage Used Cars’

China’s Intense EV Price War Taking a Toll on Car Dealers

BYD’s Big Gains Give Chinese EV Rivals a Giant Headache