China’s clampdown on exports of heavy rare earth metals could pour cold water on Washington’s push to build an alternative supply chain for the super-strong magnets that power everything, from defence technology and electric vehicles, to electronics and wind turbines.

The United States and its allies have been scrambling to create an alternative supply chain for years, but that push slowed this year with China imposing strict licensing requirements on exports of several heavy rare earths in April.

Two of these elements — dysprosium and terbium — are vital for manufacturing heavy rare earth magnets that are essential to high-tech sectors by helping the magnets retain their magnetic qualities under high temperatures, such as in EV engines.

Also on AF: Yttrium is Latest Rare Earth Concern as Global Supplies Fall

But those elements are, so far, only available in scarce quantities in the US, analysts say.

For instance, the Mountain Pass mine in California operated by rare earth developer MP Materials — which is leading the US push to create a supply chain outside of China — contains only traces of dysprosium and terbium.

MP says it has stockpiled several hundred tons of medium and heavy rare earth concentrate in preparation for magnet production but, according to the company’s website, this only contains 4% dysprosium and terbium.

“MP Materials may have a formidable challenge,” said Ilya Epikhin, senior principal with consultants Arthur D. Little. “They’ll need to go to Brazil or Malaysia, or some African states to find those resources, but it can take a lot of time.”

MP is a high-profile example of the impact of continued dependency by the West on China for heavy rare earth processing. According to consultancy Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, the West will still rely on China for 91% of its heavy rare earths needs by 2030, down only slightly from 99% in 2024.

China’s April restrictions have in some cases suspended operations at auto plants.

It’s all about the ‘heavies’

The proportion of heavy rare earths in deposits is much smaller than the other elements used in magnets, with the relative ratio of heavy rare earths in global mines only half of their relative ratio in permanent magnets.

The scarcity of heavy rare earths outside of China is evident in the price of dysprosium oxide in Rotterdam at $900 per kg, more than triple the price in China of $255, according to data provider Fastmarkets.

“If you talk about critical resources, it’s really the heavies, the heavies, the heavies – all the rest we will get,” said Erik Eschen, CEO of Germany’s Vacuumschmelze (VAC), one of the few rare earth magnet producers outside China.

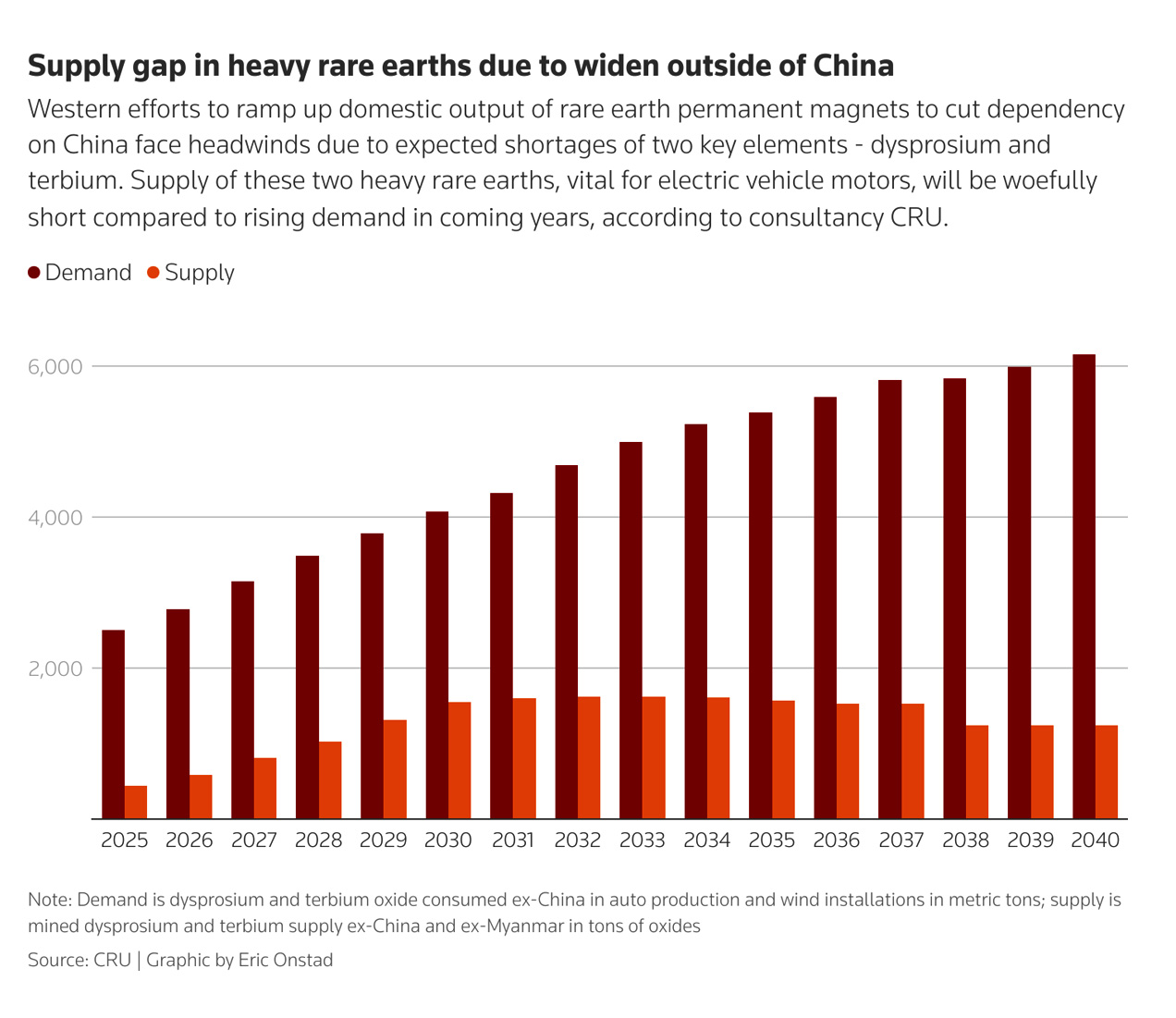

Magnet production capacity outside of China and Japan is expected to hit 70,000 metric tons a year by 2030, which would need 1,650 tons a year of dysprosium oxide, according to critical minerals consultancy Adamas Intelligence.

“Heavies are definitely the next piece of the puzzle that needs to be dealt with to unlock widespread Western magnet production at scale,” said Adamas managing director Ryan Castilloux.

MP and VAC both say they are well-positioned to secure supplies for heavies. But despite that, and a flurry of recent deals, mines outside of China are forecast to meet only 29% of the heavy rare earths consumed outside China in the auto and wind sectors by 2035, according to data from London-based commodity consultancy CRU.

“To close this gap, more mine supply will be needed with costs higher than the current supply base,” Piyush Goel, an critical metals consultant at CRU, said.

Malaysia in spotlight

The two biggest Western firms in the sector, MP Materials and Lynas Rare Earths of Australia, are both looking for additional ore to process since their own mines are not rich enough in heavy elements.

That push has put another Asia nation — Malaysia — in the spotlight.

Lynas kicked off heavy rare earth separation earlier this year in Malaysia, becoming the world’s first such producer outside China.

The Australian group announced last month it would expand output of heavy rare earths to 250 metric tons of dysprosium and 50 tons of terbium a year, but gave no timeline, saying it depended on regulatory approvals.

CEO Amanda Lacaze told analysts on a call on October 30 that Lynas planned to source heavy rare earths both from its own Mt. Weld mine in Australia and from Malaysia, where its processing plant is located.

“We have a team whose job it is to work with various Malaysian partners on that development process.”

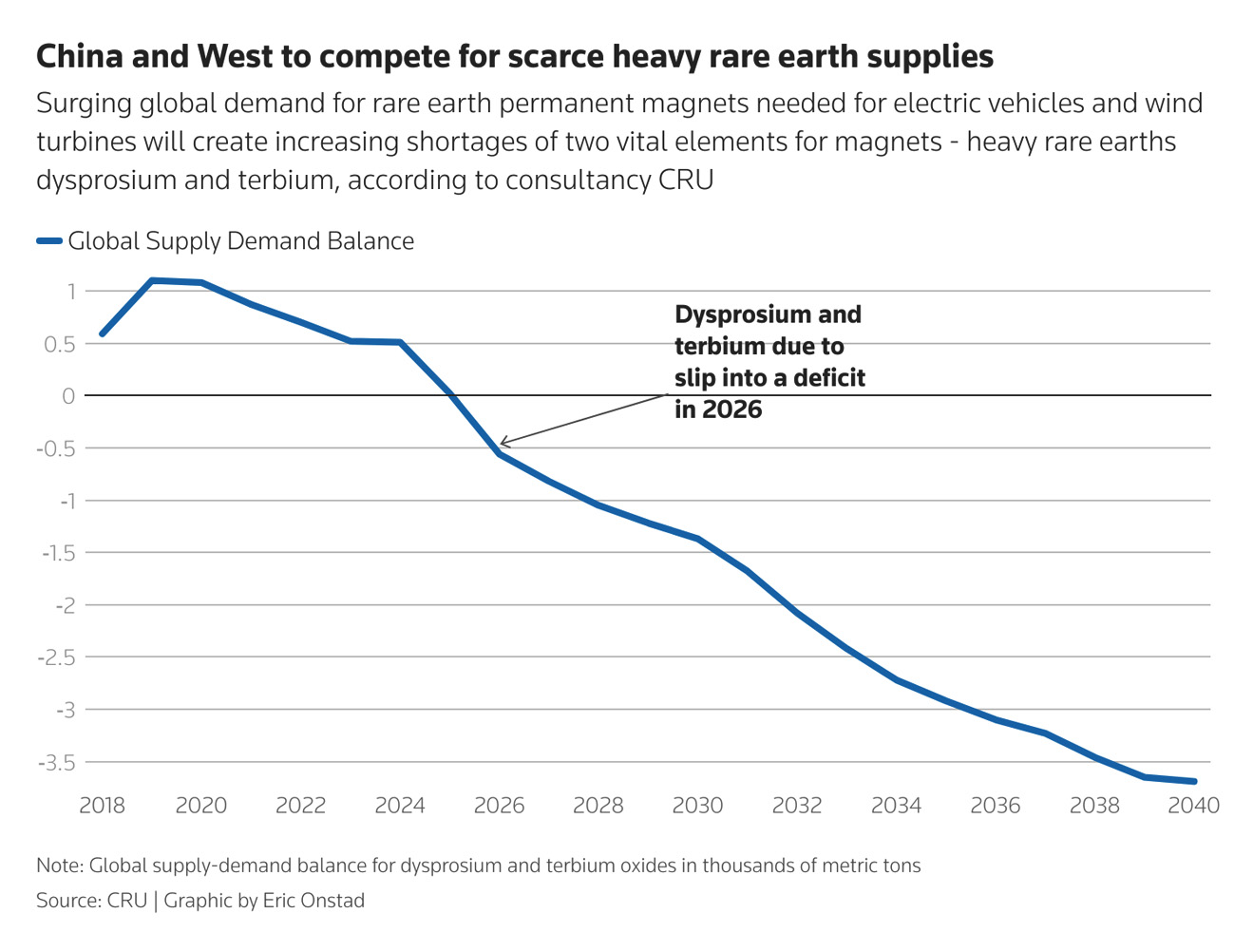

This contrasts with a global deficit forecast by CRU by 2035 of 2,920 tons in the supply/demand balance of dysprosium and terbium oxides. But it is worth nothing that any new project or processing facility for heavy rare earths will take many years to come to fruition.

Higher costs than China, environmental challenges

Brazil is also emerging as a major heavy rare earth (HREE) ore exporter, but the real challenge lies in processing capacity, said Neha Mukherjee, a rare earths analyst with Benchmark Mineral Intelligence.

“While the technology for HREE refining is expected to be available globally by 2029, costs outside of China remain 5–7 times higher,” Mukherjee said.

Higher amounts of heavy rare earths are found in ionic clay mine deposits, where the standard extraction technique involves flushing the deposit with chemicals, which in Myanmar has caused contamination of water supplies and deforestation.

Western miners say they use environmentally-friendly extraction methods, but they have sometimes met with scepticism and opposition by residents to mine plans.

Rare earth mining of deposits from monazite ore includes radioactive elements uranium and thorium, which can be difficult to dispose of safely.

“A key bottleneck for new production will be the higher negative impact of heavy rare earth mining and processing on the local environment,” CRU’s Goel said.

Some companies, including VAC, have produced magnets without heavy rare earths, but they have limited applications, such as slow-moving wind turbines, said Eschen.

“The moment you go into other applications, for example, a motor for EVs, turning very fast, going 120, 140 degrees Celsius, then you need the heavies.”

- Reuters, with additional editing by Vishakha Saxena

Also read:

Rare Earth And The US-China Powerplay

Trump Taps Southeast Asia For Rare Earths Amid China Uncertainty

Trump Cuts US Tariffs to 47%, Xi Vows to Ease Rare Earth Curbs

China Making Exports Of Rare Earth Magnets ‘Increasingly Difficult’

US May ‘Extend Tariff Truce’ If China Delays New Rare Earth Rule

China Did Not Agree to Military Use of Rare Earths, US Says

Carmakers Stressed by China’s Curbs on Critical Mineral Exports

China Export Curbs on Rare Earth Magnets: a Trade War Weapon

China Sets up Tracking System to Trace Its Rare Earth Magnets

China’s Critical Minerals Blockade Risks Global Chip Shortage

Lessons From Japan on Tackling China’s Rare Earth Dominance