Thailand has endured a series of what the Chinese would call “black swan” events – unexpected traumas – that have clouded the country’s political and economic outlook this year.

They include a huge earthquake in Myanmar in March, which caused the collapse of a 30-storey tower block under construction in Bangkok, the kidnap of a Chinese actor by human traffickers linked to a scam centre also in Myanmar and military clashes on its 800km border with Cambodia in late July.

All of these dramas have undermined its usually booming tourism industry, which the Bank of Thailand said generated about 2 trillion baht (11% of GDP) and employed more than 7 million people in 2019, about one in five of all workers across the country.

ALSO SEE: Trump’s Tariffs Spur Calls to Boycott American Goods in India

Many of the traumas that have rocked the country stem from beyond its borders. Thailand is situated in a region that is struggling to cope with problems both old and new. Yet, compared with some of its neighbours, the Thais are managing and will rise again. People in Myanmar, however, are in desperate need of help.

One of ‘oldest’ and most troubling issues on mainland Southeast Asia has been the Myanmar military and its long-held belief that it must take charge – to tame the many ethnic groups longing for a federal democratic system that would give them a greater say on the development of their traditional lands, in the northern ‘horseshoe’ surrounding the Burman central plains.

Having enjoyed close to a decade of relative freedom and economic growth since Aung San Suu Kyi was first elected to government in April 2012, tens of millions of its citizens are staunchly opposed to any return to military rule. A flood of young Burmese have joined a brutal conflict – the most intense and wide-ranging fighting since World War II, which has raged for four and a half years since Suu Kyi was ousted by army chief Min Aung Hlaing in February 2021.

‘Disaster loop’

The humanitarian impact has been devastating, with the war displacing 3.4 million people even before the 7.7 magnitude quake on March 28, which claimed over 3,800 lives and “cracked, crumbled or completely flattened” close to 52,000 homes in Naypyidaw, Sagaing, Mandalay and adjacent villages.

Damage to physical assets was estimated at close to $11 billion, while nearly 24,000 families fled Naypyidaw, the new capital, where thousands of survivors are still living in relief camps. Nearly 200 dams were cracked and 148 bridges damaged, including the vital Irrawaddy Bridge and the main highway between Yangon, Naypyidaw and Mandalay. Over 3,000 schools, hospitals and clinics need repairs.

Economic output losses from the quake will be about $2.6 billion over the year to March 2026, the World Bank said in its Myanmar Economic Monitor report in June. Inflation rose to 34% over the year to April 2025, it said, ramping up the price of food, while logistic disruption has created supply chain issues.

“Conflict, natural disasters, and the threat of conscription have all acted to drive the movement of workers into less secure and lower productivity jobs,” the report said. About 17 million people – nearly a third of all citizens – are now classed as poor, while the near-term outlook remains bleak.

The quake that levelled central Myanmar was the most severe the country had endured since 1912, yet it was just the most recent of a series of mishaps that hit the country hard. In September 2024, Yagi, one of just four category-5 super typhoons recorded in the South China Sea, roared across Hainan Island, Vietnam and northern Thailand, before claiming over 600 lives in Myanmar, according to the exile National Unity Government.

Scam centres, rare earth mining

But Myanmar and its neighbours have also been plagued by two modern-day crises that both have roots in China, which is a long-time backer of the reviled Burmese military (along with Russia).

The first is an extraordinary crime wave – scam centres set up Chinese criminal networks that flourished in areas wracked by conflict in Myanmar and the Covid-19 pandemic.

Some 300,000 people are said to work in multi-storey compounds on the Thai-Burma border near Myawaddy, and other areas in Cambodia and northern Laos, many of them detained against their will by human traffickers and tortured till they deceive citizens around the world out of large sums via a variety of investment and romance scams enabled by modern technology, social media like Facebook, and outlets that launder crypto, such as Cambodia’s Huione.

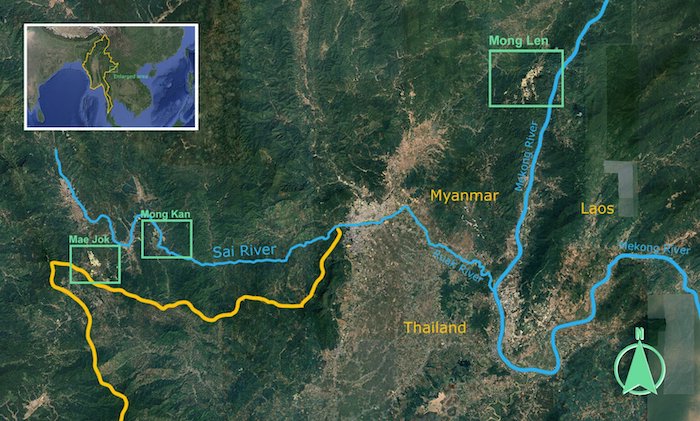

Meanwhile, the latest concern from Myanmar is the environmental risks stemming from rare earth mines. In recent years, these have become a huge health concern and ecological problem in northern Kachin state, and areas in southern Shan state, just across Thailand’s northern border.

About 1,500 people attended a rally in Chiang Rai in northern Thailand in June that called on the Thai government and China to pressure operators of the rare earth mines in Myanmar to stop polluting their rivers. Testing by Thai officials has since revealed arsenic and lead in the Kok and other rivers well over safe levels set by the World Health Organisation.

The Shan Human Rights Group and activists such as Pianporn Deetes from the International Rivers group say mines are in areas controlled by the United Wa State Army (UWSA), one of the biggest rebel groups, which has two enclaves, one near the border with China and another not far from the border with Thailand.

They are described as hard to access and dangerous, as even the Myanmar military won’t send troops into Wa territory.

Rare earth mines ‘most toxic’

Early reports suggested that river pollution came from Wa-run gold mines, but an academic told Al Jazeera that water samples taken from the Kok river in June had a “fingerprint” of heavy metals that showed 60-70% of the toxic substances in the water came from the mining of rare earth minerals.

Satellite images on Google Earth showed two new mine sites were developed over in recent years in the Wa area near the Thai border, while another 26 mines were in the Wa enclave by the Chinese border.

More concerning was reports that there is no environmental monitoring of these mines or regulations on the use of chemicals used to draw the rare earth elements out in leaching pools at the mine sites, plus reports of mine workers “dying in unusually high numbers.”

In June, the Chinese embassy in Thailand responded to these reports by saying Chinese companies operating abroad had to follow local regulations, and that “China was open to cooperating with Mekong River countries to protect the local environment.”

Thailand has also said it is working with China and Myanmar to try to solve the problem. However, with the Pheu Thai coalition facing court cases that could end the Shinawatra family’s hold on political power, plus serious strife on the Cambodian border, some observers fear the government may be too distracted to devote much effort to resolve this issue.

- Jim Pollard

ALSO SEE:

Wa Army Controlling New Rare Earth Mines in Northeast Myanmar

Thailand Plans Dams to Clean Myanmar Gold Mines’ Toxic Runoff

Cambodian Scam Centres Straining Ties With States Near And Far

China Halts Rare Earth Exports, Warns US on Deep-Sea Metals ‘Plan’

Thousands in Limbo as Thailand Fights Scam Hubs on Two Fronts

China Rare Earth Mines ‘Poisoning’ Northern Myanmar – Report

Suu Kyi Adviser Calls For Sanctions on Myanmar’s Central Bank

UN Rapporteur Calls on Thai Banks to Stop Aiding Myanmar Junta

Scamming Compounds in SE Asia Stole $64 Billion in 2023: Report