An uptick in mining for gold and rare earths — largely backed by China — is leaching poisonous chemicals into rivers that are the lifeline of Southeast Asia, effectively putting global food supplies at risk of contamination.

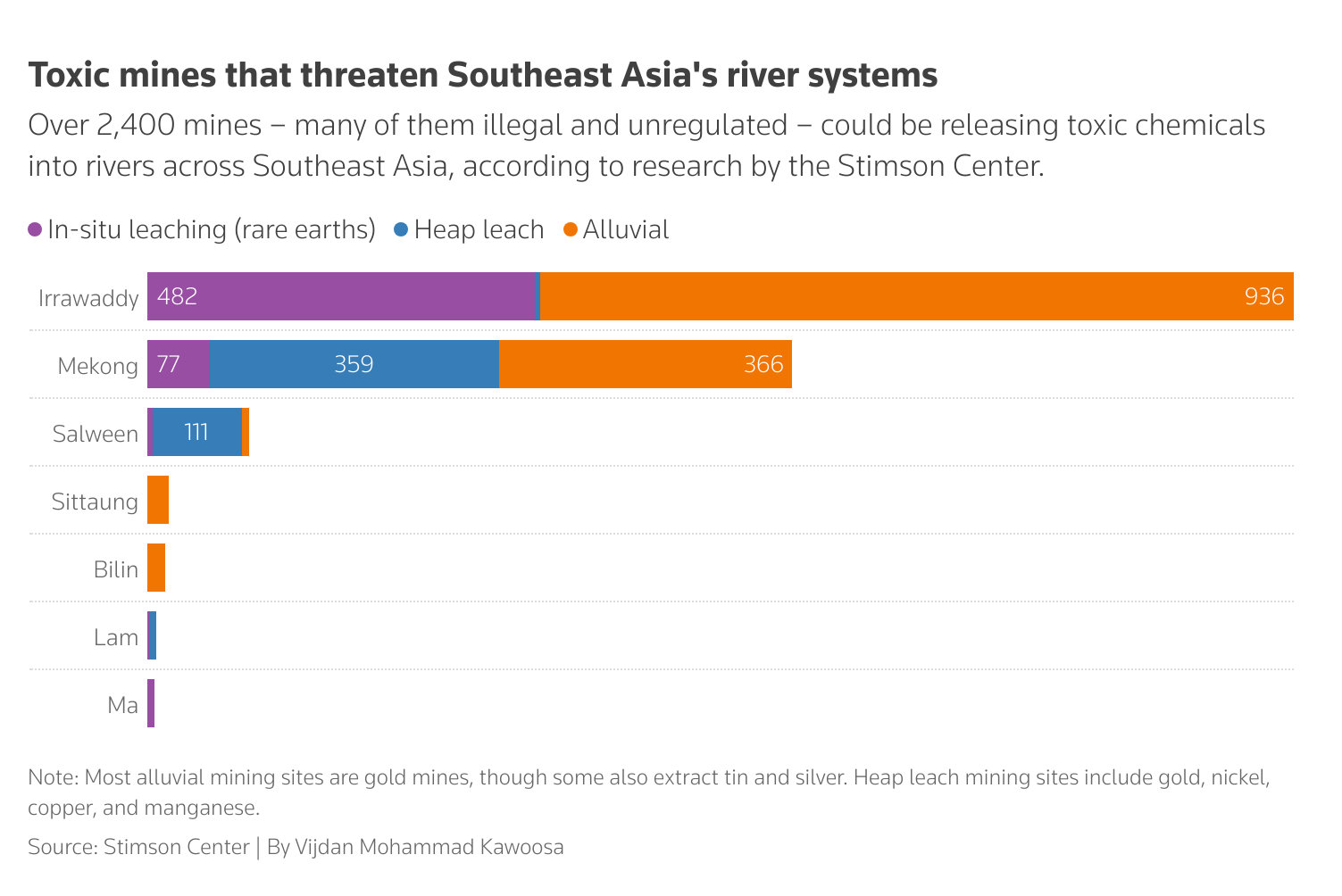

Across mainland Southeast Asia, more than 2,400 mines – many of them illegal and unregulated – are believed to be releasing deadly chemicals such as cyanide and mercury into river water, according to research released on Monday by the Stimson Center, a US-based think tank.

“The scale is something that’s striking to me,” said Brian Eyler, senior fellow at Stimson, noting that scores of tributaries of major rivers like the Mekong, the Salween and the Irrawaddy are probably highly contaminated.

Also on AF: US Offering Big Money to Nab Southeast Asian Scam Bosses

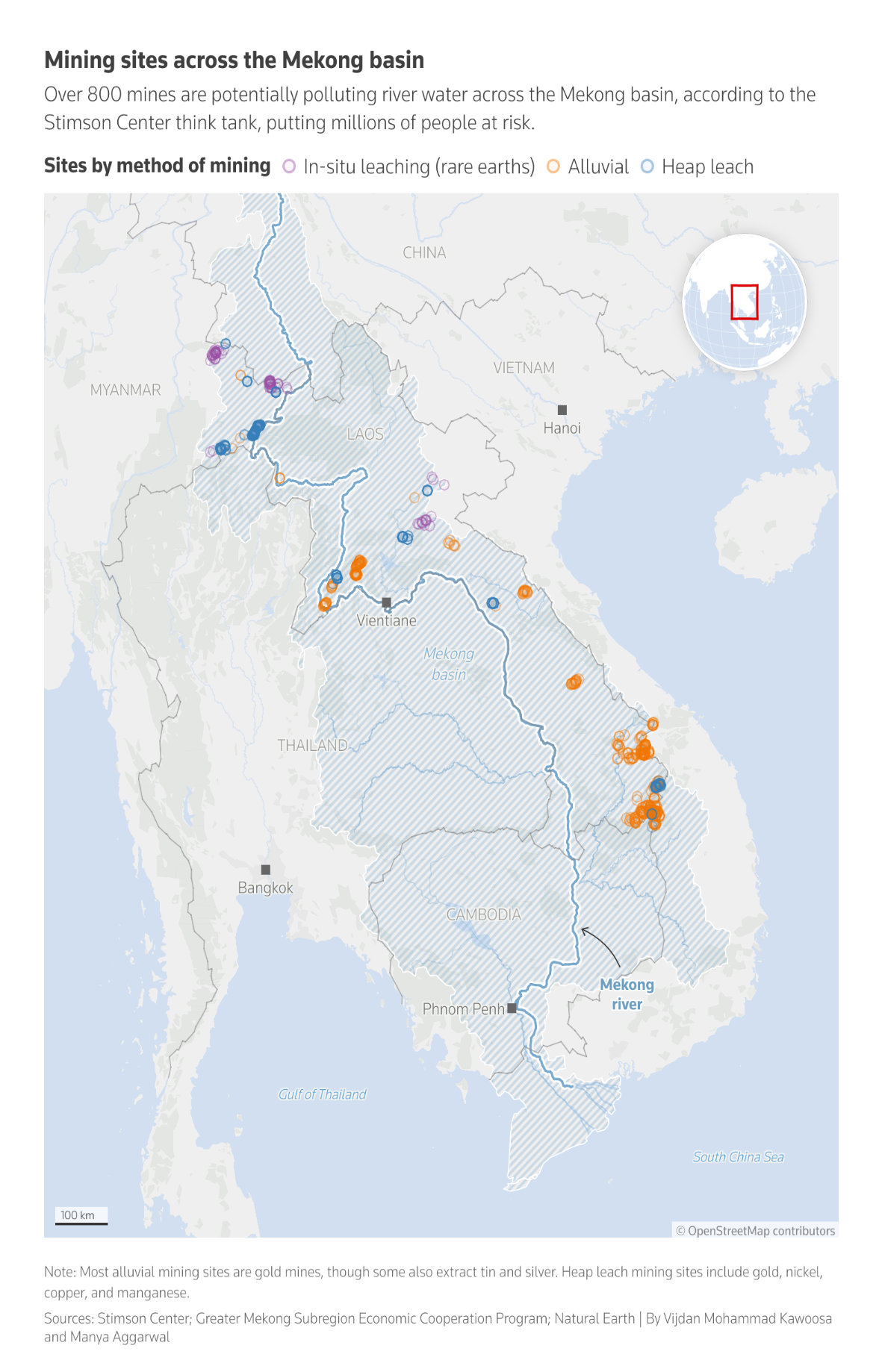

The Stimson report marks the first comprehensive study of potentially polluting mines in mainland Southeast Asia. Researchers analysed satellite imagery to identify mining activity, including 366 alluvial mining sites, 359 heap leach sites and 77 rare earth mines draining into the Mekong Basin.

Most alluvial mining sites are gold mines, though some also extract tin and silver. Heap leach mining sites include those for gold, nickel, copper, and manganese extraction.

Poisoning Southeast Asia’s lifelines

The Mekong is Asia’s third-largest river and supports the livelihood of more than 70 million people, as well as the global export of farm and fisheries products. It was previously perceived to be a clean river system, Eyler said.

“Because so much of the Mekong Basin is essentially ungoverned by national laws and sensible regulations, the basin is unfortunately ripe for this kind of unregulated activity to occur at a high level of intensity and the huge scale that our data reveals,” he said.

The toxic chemicals released through unregulated rare earths mining include ammonium sulphate, and sodium cyanide and mercury, which are used for two different types of gold mining, according to Stimson researchers.

In northern Thailand, authorities warned residents as far back in April to stop using waters of the Kok River for farming because of concerns over contamination. The Kok flows down from Myanmar into Thailand before joining with the Mekong, which cuts its way right through mainland Southeast Asia.

Farmers in the area have since been forced to use groundwater to irrigate their crops. Meanwhile, prices at local fish markets have also fallen as locals rarely eat river fish due to fears of contamination. Even elephant trainers in the area have reported that the animals developed skin infections from contact with the contaminated river.

Experts note, meanwhile, that damage from the contamination is not just limited to the millions of people who live along the Mekong in Southeast Asia. It also creates health risks for consumers elsewhere.

“There is not a major supermarket in the US that doesn’t have products from the Mekong Basin, including shrimp, rice and fish,” Eyler said.

China-backed mining

The emergence of new China-backed rare earth mines in eastern Myanmar, not far from the mountainous border with Thailand, initially set off concerns among researchers of the danger of downstream pollution along the Kok River, including areas like Tha Ton.

The contamination pattern on samples from the Kok River shows the presence of arsenic – linked to rare earth and gold mining – alongside heavy rare earths like dysprosium and terbium, said Tanapon Phenrat of Thailand Science Research and Innovation, a Thai government research agency.

“It has only been two years since the rise of rare earth and gold mining in Myanmar at the Kok River’s source,” said Tanapon, who conducted testing of the waters this year. He warned of a sharp rise in contamination levels unless mining is stopped. Tanapon was not involved in the Stimson study.

Myanmar, which erupted in conflict after the military seized power in 2021, is one of the world’s largest producers of heavy rare earths, critical minerals infused into magnets that power the likes of wind turbines, electric vehicles and defence systems.

From mining sites in Myanmar, the raw material is transported for processing to China, which has a monopoly of production of these vital magnets, with Beijing deploying rare earths as leverage in its tariff war with the US.

Mines across Myanmar and Laos use in-situ leaching for rare earth elements that was initially developed within China, according to Stimson’s Eyler.

“In general, Chinese nationals work on these mines as managers and technical experts,” he said.

In response to questions from Reuters, China’s foreign ministry claimed it was not aware of the situation.

“The Chinese side has consistently required overseas Chinese enterprises to conduct their production and business operations in accordance with local laws and regulations, and to adopt stringent measures to protect the environment,” it said.

Locals desperate for intervention

The Thai government has established three new task forces to coordinate international cooperation, monitor the mines’ health impact and secure alternative supplies for communities along the Kok, Sai, Mekong and Salween rivers, Deputy Prime Minister Suchart Chomklin said.

In northern Tha Ton, signs still hang on a bridge over the Kok River, calling for authorities to shut down the rare earths mines upriver. Local farmers are also desperate for action to shut down the mines.

“I just want the Kok River to be the way it used to be – where we could eat from it, bathe in it, play in it, and use it for farming,” said 59-year-old farmer Tip Kamlu, who has irrigated her fields with the waters of the Kok for most of her life.

“I hope someone will help make that happen.”

- Reuters, with additional editing by Vishakha Saxena

Also read:

Fears For The Mekong After 27 Rare Earth Mines Found in Laos

Trump Taps Southeast Asia For Rare Earths Amid China Uncertainty

Wa Army Controlling New Rare Earth Mines in Northeast Myanmar

Thailand Plans Dams to Clean Myanmar Gold Mines’ Toxic Runoff

China Plunders Rare Earth Minerals as Myanmar’s Civil War Rages

China Rare Earth Mines ‘Poisoning’ Northern Myanmar – Report

Rare Earth And The US-China Powerplay